Circe: Franz Von Stuck 1913

Circe, Miller's second novel, was released on April 10, 2018.[11] The book is told from the perspective of Circe, an enchantress in Greek mythology who is featured in Homer's Odyssey. Circe was ranked the second-greatest book of the 2010s in Paste.[12] An 8-part miniseries adaptation of the book has been greenlit for HBO Max.[13]

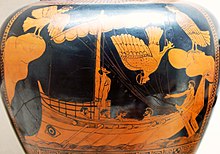

Latinized form of Greek Κίρκη (Kirke), possibly from κίρκος (kirkos) meaning "hawk". In Greek mythology Circe was a sorceress who changed Odysseus's crew into hogs, as told in Homer's Odyssey. Odysseus forced her to change them back, then stayed with her for a year before continuing his voyage.

In the house of Helios, god of the sun and mightiest of the Titans, a daughter is born. But Circe is a strange child - not powerful, like her father, nor viciously alluring, like her mother. Turning to the world of mortals for companionship, she discovers that she does possess power - the power of witchcraft, which can transform rivals into monsters and menace the gods themselves.

Threatened, Zeus banishes her to a deserted island, where she hones her occult craft, tames wild beasts and crosses paths with many of the most famous figures in all of mythology, including the Minotaur; Daedalus and his doomed son, Icarus; the murderous Medea; and, of course, wily Odysseus.

But there is danger, too, for a woman who stands alone, and Circe unwittingly draws the wrath of both men and gods, ultimately finding herself pitted against one of the most terrifying and vengeful of the Olympians. To protect what she loves most, Circe must summon all her strength and choose, once and for all, whether she belongs with the gods she is born from or the mortals she has come to love.

With unforgettably vivid characters, mesmerizing language and pause-resisting suspense, Circe is a triumph of storytelling, an intoxicating epic of family rivalry, palace intrigue, and love and loss as well as a celebration of indomitable female strength in a man's world.

Perdita Weeks was born on December 25, 1985 in Cardiff, Wales as Perdita Rose Annunziata Weeks. She is an actress, known for As Above, So Below (2014), Hamlet (1996) and Spice World (1997). She has been married to Kit Frederiksen since October 4, 2012. They have two children. See full bio » Perdita (Latin for "lost"), may refer to:

Odysseus' account of his adventures

Odysseus recounts his story to the Phaeacians. After a failed raid, Odysseus and his twelve ships were driven off course by storms. Odysseus visited the lotus-eaters who gave his men their fruit that caused them to forget their homecoming. Odysseus had to drag them back to the ship by force.

Afterwards, Odysseus and his men landed on a lush, uninhabited island near the land of the Cyclopes. The men then landed on shore and entered the cave of Polyphemus, where they found all the cheeses and meat they desired. Upon returning home, Polyphemus sealed the entrance with a massive boulder and proceeded to eat Odysseus' men. Odysseus devised an escape plan in which he, identifying himself as "Nobody," plied Polyphemus with wine and blinded him with a wooden stake. When Polyphemus cried out, his neighbors left after Polyphemus claimed that "Nobody" had attacked him. Odysseus and his men finally escaped the cave by hiding on the underbellies of the sheep as they were let out of the cave.

As they escaped, however, Odysseus, taunting Polyphemus, revealed himself. The Cyclops prays to his father Poseidon, asking him to curse Odysseus to wander for ten years. After the escape, Aeolus gave Odysseus a leather bag containing all the winds, except the west wind, a gift that should have ensured a safe return home. Just as Ithaca came into sight, the sailors opened the bag while Odysseus slept, thinking it contained gold. The winds flew out and the storm drove the ships back the way they had come. Aeolus, recognizing that Odysseus has drawn the ire of the gods, refused to further assist him.

After the cannibalistic Laestrygonians destroyed all of his ships except his own, he sailed on and reached the island of Aeaea, home of witch-goddess Circe. She turned half of his men into swine with drugged cheese and wine. Hermes warned Odysseus about Circe and gave Odysseus an herb called moly, making him resistant to Circe's magic. Odysseus forced Circe to change his men back to their human form, and was seduced by her.

They remained with her for one year. Finally, guided by Circe's instructions, Odysseus and his crew crossed the ocean and reached a harbor at the western edge of the world, where Odysseus sacrificed to the dead. Odysseus summoned the spirit of the prophet Tiresias and was told that he may return home if he is able to stay himself and his crew from eating the sacred livestock of Helios on the island of Thrinacia and that failure to do so would result in the loss of his ship and his entire crew. For Odysseus' encounter with the dead, see Nekuia.

Returning to Aeaea, they buried Elpenor and were advised by Circe on the remaining stages of the journey. They skirted the land of the Sirens. All of the sailors had their ears plugged up with beeswax, except for Odysseus, who was tied to the mast as he wanted to hear the song. He told his sailors not to untie him as it would only make him drown himself. They then passed between the six-headed monster Scylla and the whirlpool Charybdis. Scylla claims six of his men.

Next, they landed on the island of Thrinacia, with the crew overriding Odysseus's wishes to remain away from the island. Zeus caused a storm which prevented them leaving, causing them to deplete the food given to them by Circe. While Odysseus was away praying, his men ignored the warnings of Tiresias and Circe and hunted the sacred cattle of Helios. The Sun God insisted that Zeus punish the men for this sacrilege. They suffered a shipwreck and all but Odysseus drowned. Odysseus clung to a fig tree. Washed ashore on Ogygia, he remained there as Calypso's lover.

Circe Offering the cup to Odysseus, John Waterhouse, 1891.

Pasiphaë:

Circe’s sister, a powerful witch who marries Zeus’ mortal son Minos and becomes queen of Crete. She has several children with him, including Ariadne and Phaedra, and also contrives to become pregnant by a sacred white bull, giving birth to the Minotaur.

Helen Macdonald’s “H is for Hawk” arrives bearing accolades, including the Costa Prize for book of the year in Britain, where the memoir was first published last year. The recognition is well-deserved: The book is an elegantly written amalgam of nature writing, personal memoir, literary portrait and an examination of bereavement. Its considerable accomplishment is to hold all these parts in balance.

Macdonald was in her late 30s and a lecturer at Cambridge when her father, a photojournalist, died suddenly, and young, of what appears to have been a heart attack. The arc of the book — its flight — originates in the shock of that loss.

Macdonald found herself withdrawing from work, friends, family, human interaction. She was defined by grief. In this state, she seized upon a very personal refuge and also began to track a literary figure. From early childhood, she had been obsessed with falconry. She read the classic texts, absorbed precociously the upper-class terms associated with falconry and later flew her own falcons. While still young, she came upon a curious book called “The Goshawk,” an early work by T.H. White , who was later celebrated for “The Sword in the Stone” (1938) and “The Once and Future King” (1958). Macdonald’s book begins a fascinating dance with “The Goshawk” and its author.

Like Macdonald, White was at one time withdrawing from the world. In the mid-1930s he was a desperately unhappy, fearful man, anguished about his homosexuality and an awareness of his own sadism. White abruptly left his own teaching position and moved into a cottage at the edge of the school grounds where, he decided, he would deploy extremes of patience and calm to train a goshawk. That he had no idea how to do this and made a fearful mess of it, damaging both himself and his hawk, is a key part of Macdonald’s book.

This link (two writers, two wounded withdrawals) might feel precious or contrived were it not so clearly the case that Macdonald’s decision to buy and train not a falcon but a far more formidable goshawk (a bird she had never loved) sprang directly from her engagement with White and the book he wrote — a book that had mystified and angered her as a child.

The threads are woven skillfully. We engage with the modern woman coping (badly, she makes clear) with loss, and also with T.H. White, beset by many demons. Both trying to become one with a raptor, to share in its force and freedom while engaged in the process of taking away that freedom. (By Guy Gavriel Kay February 26, 2015 WA Post)

The Once and Future King is a work by T. H. White based upon the 1485 book Le Morte d'Arthur by Sir Thomas Malory. It was first published in 1958. It collects and revises shorter novels published from 1938 to 1940, with much new material.

Le Morte d'Arthur (originally spelled Le Morte Darthur, ungrammatical[1] Middle French for "The Death of Arthur") is a 15th-century Middle English prose reworking by Sir Thomas Malory of tales about the legendary King Arthur, Guinevere, Lancelot, Merlin and the Knights of the Round Table—along with their respective folklore. In order to tell a "complete" story of Arthur from his conception to his death, Malory compiled, rearranged, interpreted and modified material from various French and English sources. Today, this is one of the best-known works of Arthurian literature. Many authors since the 19th-century revival of the legend have used Malory as their principal source.

King Arthur (Welsh: Brenin Arthur, Cornish: Arthur Gernow, Breton: Roue Arzhur) was a legendary British leader who, according to medieval histories and romances, led the defence of Britain against Saxon invaders in the late 5th and early 6th centuries. The details of Arthur's story are mainly composed of folklore and literary invention, and modern historians generally agree that he is unhistorical.[2][3] The sparse historical background of Arthur is gleaned from various sources, including the Annales Cambriae, the Historia Brittonum, and the writings of Gildas. Arthur's name also occurs in early poetic sources such as Y Gododdin.[4]

Arthur is a central figure in the legends making up the Matter of Britain. The legendary Arthur developed as a figure of international interest largely through the popularity of Geoffrey of Monmouth's fanciful and imaginative 12th-century Historia Regum Britanniae (History of the Kings of Britain).[5] In some Welsh and Breton tales and poems that date from before this work, Arthur appears either as a great warrior defending Britain from human and supernatural enemies or as a magical figure of folklore, sometimes associated with the Welsh otherworld Annwn.[6] How much of Geoffrey's Historia (completed in 1138) was adapted from such earlier sources, rather than invented by Geoffrey himself, is unknown.

Although the themes, events and characters of the Arthurian legend varied widely from text to text, and there is no one canonical version, Geoffrey's version of events often served as the starting point for later stories. Geoffrey depicted Arthur as a king of Britain who defeated the Saxons and established a vast empire. Many elements and incidents that are now an integral part of the Arthurian story appear in Geoffrey's Historia, including Arthur's father Uther Pendragon, the magician Merlin, Arthur's wife Guinevere, the sword Excalibur, Arthur's conception at Tintagel, his final battle against Mordred at Camlann, and final rest in Avalon.

The 12th-century French writer Chrétien de Troyes, who added Lancelot and the Holy Grail to the story, began the genre of Arthurian romance that became a significant strand of medieval literature. In these French stories, the narrative focus often shifts from King Arthur himself to other characters, such as various Knights of the Round Table. Arthurian literature thrived during the Middle Ages but waned in the centuries that followed until it experienced a major resurgence in the 19th century. In the 21st century, the legend lives on, not only in literature but also in adaptations for theatre, film, television, comics and other media.

The first collection of Joseph Campbell’s writings and lectures on the Arthurian romances of the Middle Ages, a central focus of his celebrated scholarship, edited and introduced by Arthurian scholar Evans Lansing Smith, PhD, the chair of Mythological Studies at Pacifica Graduate Institute.

Throughout his life, Joseph Campbell was deeply engaged in the study of the Grail Quests and Arthurian legends of the European Middle Ages. In this new volume of the Collected Works of Joseph Campbell, editor Evans Lansing Smith collects Campbell’s writings and lectures on Arthurian legends, including his never-before-published master’s thesis on Arthurian myth, “A Study of the Dolorous Stroke.” Campbell’s writing captures the incredible stories of such figures as Merlin, Gawain, and Guinevere as well as the larger patterns and meanings revealed in these myths. Merlin’s death and Arthur receiving Excalibur from the Lady of the Lake, for example, are not just vibrant stories but also central to the mythologist’s thinking.

The Arthurian myths opened the world of comparative mythology to Campbell, turning his attention to the Near and Far Eastern roots of myth. Calling the Arthurian romances the world’s first “secular mythology,” Campbell found metaphors in them for human stages of growth, development, and psychology. The myths exemplify the kind of love Campbell called amor, in which individuals become more fully themselves through connection. Campbell’s infectious delight in his discoveries makes this volume essential for anyone intrigued by the stories we tell - and the stories behind them.

Composed in the early thirteenth century, Wolfram von Eschenbach's Parzival is the re-creation and completion of the story left unfinished by its initiator Chrétien de Troyes. It follows Parzival from his boyhood and career as a knight in the court of King Arthur to his ultimate achievement as King of the Temple of the Grail, which Wolfram describes as a life-giving Stone. As a knight serving the German nobility in the imperial Hohenstauffen period, the author was uniquely placed to describe the zest and colour of his hero's world, with dazzling depictions of courtly luxury, jousting and adventure. Yet this is not simply a tale of chivalry, but an epic quest for spiritual education, as Parzival must conquer his ignorance and pride and learn humility before he can finally win the Holy Grail.

(The middle way)

H is for Circe

H = 8

C = 3

"This winged comparison is too

swift for unripe wits."